Studying the biology of hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection and developing new therapeutics require robust experimental models. Although human liver cancer cell lines have been widely used to model HEV infection, these models have fundamental limitations. Because of extensive and long-term culturing, these cell lines harbor enormous genetic, epigenetic, and functional alterations. Thus, many important host factors and antiviral targets are likely dysregulated, compromising the authenticity in recapitulating virus-host interactions and antiviral drug assessment.

The recent advent of organoid technology provides a unique opportunity for moving the field forward. Organoids are tiny, self-organized 3D tissue cultures that are derived from adult stem cells. They are much better in recapitulating the architecture, composition, diversity, organization, and functionality of cell types of the original tissue/organ. By exploring organoids cultured from human liver tissues, researchers from Erasmus University Medical Center, the Netherlands have successfully established new models for recapitulating HEV infection.

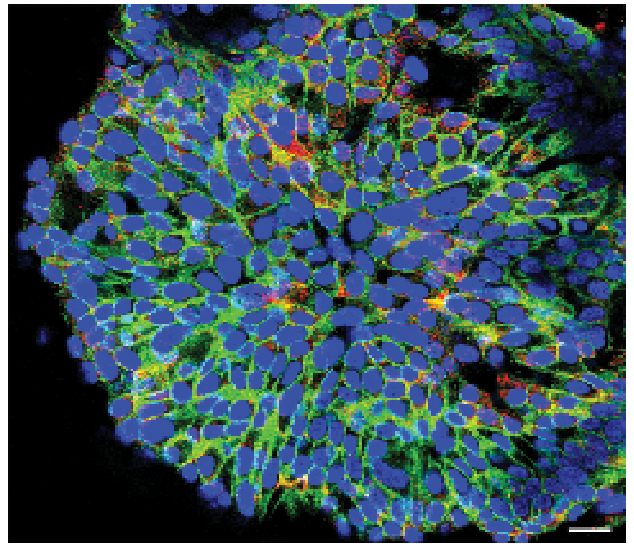

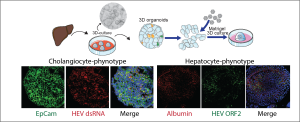

The original organoids cultured from liver tissue carry cholangiocyte-like phenotype, but they can be differentiated into hepatocyte-like phenotype in a specific culture condition. Although HEV mainly infects hepatocytes (the main cell type in the liver), infection of intrahepatic bile duct (cholangiocytes) has also been observed in HEV patients. In this study, the researchers have demonstrated successful infection of HEV in both cholangiocyte-like and hepatocyte-like organoids in 3D culture (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. HEV infection in cholangiocyte-like and hepatocyte-like organoids derived from human liver tissues in 3D culture. The virus was stained based on the viral genome (dsRNA; in red) or the viral protein (ORF2; in green).

Using a transwell system, the researchers converted 3D liver organoids into a 2D culture. They found these monolayers of organoids cells also fully support HEV infection. Interestingly, they found HEV virus particles are mainly released from the apical side (Fig. 2). This may well recapitulate how HEV viruses are released and disseminated from human body.

Figure 2. HEV infection in 2D cultured organoid cells in transwell system. Quantification of released viruses from polarized cells infected with HEV.

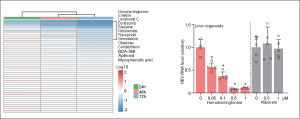

Finally, this model was used to study how HEV actively interacts with the host cells, and to screen possible anti-HEV drugs (Fig. 3). Homoharringtonine, an approved medication for treating chronic myeloid leukemia, was found to be very strong in inhibiting HEV. It is intuitive to suggest that repurposing homoharringtonine is attractive for treating HEV-infected patients with leukemia, as it can simultaneously inhibit cancer cells and the virus. But future research in animal studies are recommended to further validate the anti-HEV efficacy before clinical application.

Figure 3. Anti-HEV drug screening in liver organoids model and identification of homoharringtonine as a potent HEV inhibitor. At very low concentrations, homoharringtonine can already strongly inhibit HEV replication.

In summary, this study has successfully established human liver organoids based HEV models, and demonstrated their applications in studying virus-host interactions and antiviral drug discovery. These models could serve as innovative tools to further advance HEV research in the field. Nevertheless, the current study primarily focused on genotype 3 HEV, and modeling the infection of other genotypes remains to be investigated in future research.

This study was published in Science Advances in January, 2022. Publication link: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abj5908