Hepatitis E, an infectious disease caused by hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection is currently the major acute viral hepatitis problem worldwide. Immunocompromised individuals, such as organ transplant recipients are particularly vulnerable to chronic HEV infection. Moreover, although HEV predominantly targets liver, there is compelling evidence suggesting a causal effect causal effect between HEV infection and extra-hepatic manifestations. Recently, a German group reported that HEV can be persistently detected (>9 months) in the ejaculates of most chronic hepatitis E patients (75%, 9/12) [1, 2]. HEV RNA in the ejaculate can be significantly higher than in serum or plasma, and stool. Moreover, Enveloped HEV virions were seen in the ejaculate using immunogold electron microscopy. This group subsequently proved that HEV in patient’s ejaculate can infect PLC/PRF/5 cells indicating shedding of infectious HEV virions [2]. Such evidence observed in chronic hepatitis E patients, strongly suggesting tropism of HEV for the testis. However, direct evidence of HEV infection within the human testis is still pending, and further investigation is needed to unravel the potential interplay between the virus and the host within such tissues.

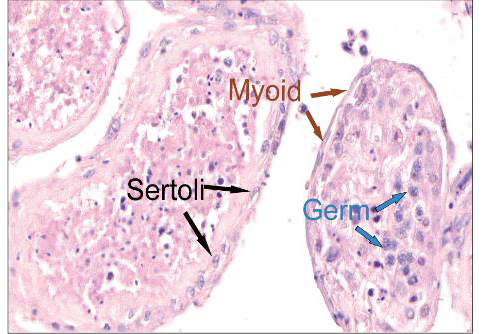

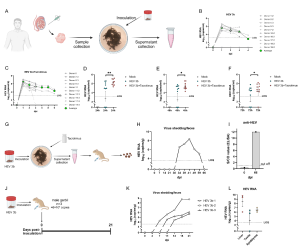

To investigate the abovementioned question, Liu and colleague[3] cultured human testicular tissues ex vivo and demonstrated HEV genotype 3 (HEV-3), but not HEV-1 or HEV-C1, can infect human testicular tissues and Sertoli cells. Treatment of tacrolimus increased the susceptibility of testis explants to HEV as all treated explants (100.0%, 10/10) showed HEV replication compared to 70% (7/10) in the untreated group. Moreover, tacrolimus-treated explants showed a significant higher HEV RNA level in the supernatants than the untreated explants. To assess the capability of testes to generate infectious HEV particles, Liu conducted experiments using gerbils, small rodents susceptible to human HEV-3. A female gerbil was intraperitoneally inoculated with the pooled supernatants collected from infected testis explants at 1 dpi. Subsequently, stable fecal virus shedding was observed started from 34 dpi, demonstrating the infectivity of viral progeny.

Next, Liu and colleagues found that primary human Sertoli cells are also susceptible to HEV-3 infection. Testicular tissues collected from chronically-infected rabbits and Mock-infected rabbits at 13 weeks post-inoculation were subjected to transcriptome analysis. Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of the down-regulated genes enriched in spermatid differentiation, spermatid development and sperm motility.

Overall, Liu and colleagues demonstrated that HEV replicates in the human testis ex vivo and infects Sertoli cells. These results underscore the need for further investigation of the impact of HEV on the male reproductive health especially in patients with chronic hepatitis E. The ex vivo model of HEV infection of the human testis they developed provides a valuable tool for the testing of therapeutic strategies and advancing our understanding of HEV infection dynamics in the male reproductive system.

Figure. HEV replication in human testicular tissues. (A) Experimental design. Testis tissues were collected from male donors and cultured as tissue explants for ex vivo infection of HEV. Supernatants were collected for HEV RNA detection. (B) HEV RNA in supernatants of human testis explants inoculated with HEV genotype 3b. (C) HEV RNA in supernatants of human testis explants inoculated with HEV genotype 3b and treated with tacrolimus. (D) Comparison of HEV RNA levels in the supernatants collected from testis explants inoculated with HEV-3b and HEV-3b treated with tacrolimus at 24 hours post-inoculation (hpi), (E) 48 hpi and (F) 72 hpi. (G-I) Supernatants collected from testis explants inoculated with HEV-3b and treated with tacrolimus were inoculated to a Mongolian gerbil. (G) Experimental design. (H) The level of fecal HEV shedding of this gerbil was monitored. (I) Detection of anti-HEV antibodies in gerbil’s serum samples at 66 dpi. (J-L) HEV-3b infection experiment in gerbils. (J) Experimental design. (K) The levels of fecal HEV shedding of gerbils were monitored. (L) HEV RNA levels in liver, testis and epididymis tissues collected at 21 dpi. dpi, day post-inoculation; HEV, hepatitis E virus; hpi, hour post-inoculation; LOQ, lower limit of quantification; Tac, tacrolimus.

Read the full article (Emerg Microbes Infect. 2024 Mar 22:2332657.): DOI: 10.1080/22221751.2024.2332657

References

- Horvatits T, Wißmann J, Johne R, Groschup MH, Gadicherla AK, Schulze Zur Wiesch J, Eiden M, et al. Hepatitis E virus persists in the ejaculate of chronically infected men. J Hepatol 2021;75:55-63.

- Schemmerer M, Luetgehetmann M, Bock H, Schattenberg J, Huber S, Polywka S, Mader M, et al. THU329 – Relevance of HEV detection in ejaculate of chronically infected patients. J Hepatol 2022:S257.

- Liu T, Cao Y, Weng J, et al. Hepatitis E virus infects human testicular tissue and Sertoli cells. Emerg Microbes Infect. Published online March 22, 2024. doi:10.1080/22221751.2024.2332657