Hepatitis E virus (HEV) genotype 3 is very common in pig farms throughout the world and pigs are an important source of human infections in industrialized countries, probably mainly by consumption of undercooked pork. Though pigs do not acquire overt symptoms from HEV infection, mitigation of HEV on pig farms is needed to reduce human exposure to this pathogen. It is needed to understand the HEV infection dynamics and potential variation in dynamics within and between farms, to come up with effective measures for mitigation.

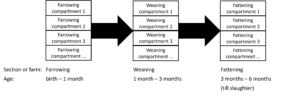

Pig farms usually consist of different farm sections for i.a. the sows and farrowing piglets, weaned piglets and fattening pigs, or farms are specialized for e.g. fattening pigs only. Within such a specialized farm (section) for fattening pigs, pigs (from ~three to ~six months of age) are kept in compartments grouped by age until the end of fattening. Pigs from the compartments that have reached the proper slaughter weight will be transported to slaughter, after which the compartments are cleaned, and new pigs of 3 months old will be delivered to the farm (section) for fattening (see fig 1. for schematic overview).

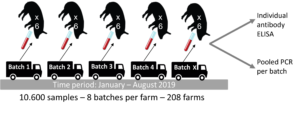

Because of this compartmentalization of farms, and effort of pig farmers to prevent pathogens to spread between the compartments, a recent study by M. Meester (DVM; MSc), Dr. Tijs Tobias and their colleagues investigated HEV prevalence on farm-level, as well as on the level of deliveries of pigs to slaughter, also called batches. The team sampled 1711 batches delivered to slaughter from 208 Dutch pig farms over a period of eight months. From each batch, ~six pigs were sampled for blood. Sera were tested individually for HEV antibodies with an ELISA, and pooled per batch to test for HEV RNA with RT-PCR (fig 2).

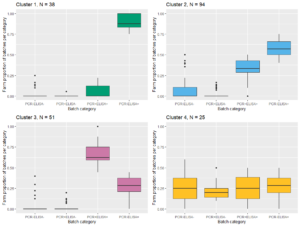

All pig farms had a least one HEV seropositive pig and the average seropositive proportion within farms was 74% (inter quartile range 67 – 87%). However, only a mean of 40% of batches per farm was PCR positive (i.e. one or more out of 6 pigs was viremic). Besides, 32% of farms delivered at least one batch that was negative according to PCR (PCR–) in addition to 5 or 6 out of 6 pigs being seronegative (ELISA–). They used the combination of PCR and ELISA results on batch-level to categorize each batch into either PCR–ELISA–; PCR+ELISA-; PCR+ELISA+; PCR–ELISA+. Presumably, the first category means that HEV transmission within the compartment is minimal or absent. The other three categories may be related to the relative age of HEV infection within a compartment, PCR+ELISA– suggesting the latest infection, and PCR–ELISA+ the earliest infection in the pigs’ life.

For every farm, the proportion of batches within each category was utilized to perform a cluster analysis. Four farm clusters were found based on these batch results. The authors discovered that cluster 1 farms almost exclusively deliver PCR–ELISA+ batches to slaughter, indicating early infection in each separate compartment. Cluster 4 farms seem the only ones that are able to prevent or delay HEV infection as most batches were classified as PCR–ELISA– and PCR+ELISA– (fig. 3).

These results are promising, because the variation in HEV infection dynamics between farms, but particularly within farms, points to the feasibility of mitigation measures that reduce human exposure to HEV via pigs. To uncover whether farm compartments can indeed remain free from HEV, the team is performing a longitudinal study on a fattening pig farm from cluster 1 and from cluster 4. Furthermore, to identify effective measures that contribute to mitigate HEV on farms, a case-control study was done in which biosecurity measures on farms with and without PCR–ELISA– batches are compared (to be submitted for publication).

This work was part of the project “HEVentie: hepatitis E virus intervention in primary pig production”. HEVentie receives financial support of the Topsector AgriFood (TKI AF 18119). Within TKI Agri&Food private partners, research institutes and government cooperate to innovations for safe and healthy food for 9 billion people on a resilient globe.

Read the full article [Vet Res. 2022 Jul 7;53(1):50]: DOI: 10.1186/s13567-022-01068-3